Shohei Ohtani's Legacy, For Me, Begins with...Charlie Hough

The Complicated Legacy of AAPI Heritage in Baseball

From Charlie Hough to Shohei Ohtani: My Dodger Life

As one of the cohosts of the Asians in Baseball podcast, I’ve been asked numerous times by friends, social media mutuals, and even ESPN, Bloomberg News, and Spectrum Sports News what it means to have Shohei Ohtani and Yoshinobu Yamamoto join the Dodgers. I haven’t been able to figure out exactly why I get emotional when asked, and I usually talk about community and Asian male identity. But I’m realizing it goes beyond that for me, a lifelong Dodger fan and 4th generation Japanese American.

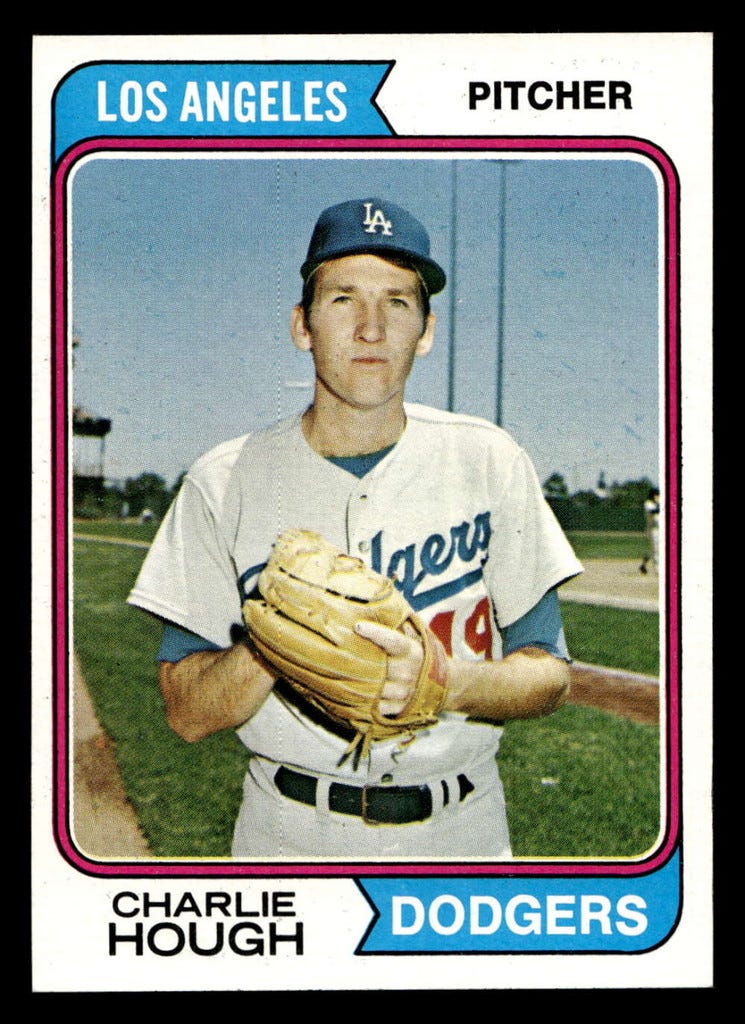

This past offseason, I went through everything all baseball fans went through, speculating where Shohei Ohtani would end up, hoping he would join my team and panicking when it looked for a minute like he was going to Toronto. And when it all played out, and Ohtani put on the Dodger cap and told us his dog’s name is Decoy, I braced for the Dodger hate, even as I felt pangs of nostalgia and pain stirring in my inner child. As for the hate: Bring it. So let me explain the inner-child part. It starts with the hazy memory of a pitcher named Charlie Hough.

In the mid-1970’s the Dodger infield defined my baseball world. Outfielder Dusty Baker would eventually become my favorite player, but I worshipped Ron Cey, Bill Russell, Davey Lopes, and Steve Garvey. I tried all their batting stances in little league, settling on something between Baker and Lopes. Something in my young mind had me gravitating towards the non-White guys, but truly I loved them all.

It became complicated because I knew they didn’t necessarily love me back. As a Japanese American kid in an all-White school in the 70’s, I knew I didn’t belong in the same world as my heroes. I didn’t look like them, even as I knew my family had been in America for at least as long as theirs. As a young kid, I knew how deep the chasm was between my world and that of Major League Baseball. It seemed absurd to even consider breaching it.

And yet, my dad took my brother and me to an autograph night at Dodger Stadium sometime in the late 70’s. Back then, they let people assemble in the outfield before the game, and the players would walk through them, stopping to take pictures with the kids. We tried to get a spot close to the line separating the people and the players, but we had to settle for being right behind other White families. Between arms and legs, I saw my favorite players walk by. Ron Cey glanced at us behind the White family and seemed to nod but didn’t address us. For those White families, the cultural gap between them and the players was simply a piece of rope. For us, it was more of a ravine. Ironically, Chavez Ravine is where Dodger Stadium is located as a legacy of cruelly booting out the Hispanic residents.

My dad had brought his fancy Nikon camera for the occasion, and I remember thinking the sight of such a cool camera would impress players. But they routinely stopped for the White family in front of us and looked right past my dad, his camera, and us after snapping pictures with the White folks. I look back at that day and truly feel for my dad, trying to flag down a player to take a picture with his young sons and being completely ignored. Honestly, it tracked with my experience as an elementary student in Arcadia, California, a city entrenched in Red Line practices until the 90’s. I was used to feeling invisible.

Russell stopped near us and went by without noticing. Steve Garvey’s chiseled chin and all-American smile seemed to float towards us. He was my favorite player at that point, and my heart raced as I watched him come closer. He stopped to greet the family in front of us, and as he finished, he noticed us sitting awe-struck behind everyone, pleading with our eyes to be noticed. My mouth went dry, and I wanted to say, “Hi Steve!” But I couldn’t find my voice. None of us could. I’ll never forget how he seemed to look right through our little Japanese American family before continuing on down the line of White people. He had been my favorite player up to that day, but after that, I had mixed feelings about him.

Those were the only faces I remember, other than one that would make me a fan for life. As the event wound down and the players started making their way back to the dugout, not a single player had stopped to say hi to us, despite my dad trying to get their attention by sticking his arm through the White family in front of us to wave down the players. And by the end, I resented the ridiculously big camera he had brought. It seemed to represent failure after great effort.

As my brother and I sat there on the incredible outfield grass, I heard my dad call out, “Excuse me, Mr. Hough? Would you take a picture with my boys?”

A smiling Charlie Hough said, “Sure!” Hough was a knuckleball relief pitcher at the time, and he extended a hand across the aforementioned chasm, across the divide between our family and Major League Baseball and knelt down beside my brother and me to take a picture. He instantly became one of my favorite players for the rest of his long career. It wasn’t just that he was the only player that day to stop to acknowledge us. He looked directly at us and smiled broadly, putting his arms around my brother and me for the picture. It sounds ridiculous to say this today, but on that day, Charlie Hough made us feel like we existed in Los Angeles. Up to that moment, it had made perfect sense that the White family in front of us had gotten pictures and autographs with the players and we hadn’t. But Hough changed that for us in a singular moment of shared humanity.

Charlie Hough would be traded to the Texas Rangers a few years later, beginning the mass shift in the Dodgers who would also let my beloved infield go. Once Garvey went to the Padres in 1984, I was done with baseball for a while, pursuing guitar and girls. But I kept track of Hough’s career that saw him become a premier starter and All-Star.

I didn’t even watch the 1988 miracle season, and when Kirk Gibson limped around the bases in game one of the World Series, I heard the cheers and screams coming from the UC San Diego cafeteria, but I didn’t really care. Baseball and the Dodgers were a nostalgia trip for me, but my developing sense of self as an Asian American felt it could never be important to me again.

But baseball ran deep in my blood. My dad’s dad had been a semi-pro player in the 1930’s, and he taught my dad and uncle to play in Pasadena. I knew Jackie Robinson was from Pasadena and that my grandpa, dad, and uncle played on the same fields as him. My grandpa taught me how to wind up and pitch in his driveway when I was 8. So, it was just a matter of time before I returned to baseball while at UC San Diego. It was Tony Gwynn who brought me back.

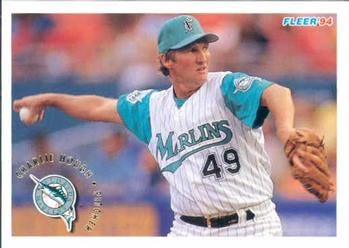

In 1994, while living in San Francisco, I bought a single rather expensive ticket behind home plate to see the Giants play the Florida Marlins at Candlestick Park, just so I could see a then 46 year-old Charlie Hough start the game. It was Hough’s final season but watching him that day brought me right back to that day at Dodger Stadium, and I wished I could tell him what it meant to me to see him in his final season. Dusty Baker was the new manager of the Giants, and despite growing up hating the Giants, I became a Giants fan. For Dusty.

.

But the Dodgers were still my team, and the next year, 1995, they signed Hideo Nomo. I can’t begin to express what it meant to me to see Nomo-Mania blow up. The team that gave us Jackie Robinson, one of my childhood heroes, had signed the first ever star from Japan. I was in my mid-20’s, but I felt like a kid again, watching every game I could from the Bay Area, even traveling back to LA to see Nomo pitch a few times. Even though Nomo was from Japan, and I was a 4th generation Japanese American, it finally felt like the baseball world beyond Charlie Hough, saw me. The concession stands sold sushi, and the diverse crowds at Dodger Stadium going wild for every Nomo strikeout brought me to tears.

Before I get to the big Ohtani finish you are likely now expecting, let me tell one more sad story from the past.

I went to a Dodger game last year with some Japanese American friends, and one of them told me a story about a famous Dodger that broke my heart. My friend and his brother were waiting near the visiting bullpen at San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium in the mid-70’s. They were thrilled to see a big-time Dodger star signing autographs for the few Dodgers fans. They waited patiently with their baseballs, and when they got to the front, the player looked at them, uttered a swear word, made a racist comment, and stormed back into the dugout. As they slumped back to their seats, their father demanded to know why they didn’t get an autograph, and when they told him what happened, he was furious. As my friend and his brother retook their seats, feeling ashamed and dejected, they looked down to the bullpen to see that the line had re-formed, and the star Dodger was back signing autographs for the White kids. My friend’s father was angry about this incident for the rest of his life. And while he still feels resentment every time he looks at the autograph line, my friend still follows the Dodgers and goes to games.

But, a fan’s love for baseball and a favorite team runs deep. It can overcome even the most horrific memories of racism and the knowledge that baseball doesn’t always love you back.

Even before Ohtani put on the Dodger cap, we’ve seen Asian players succeed in the big leagues. Ichiro, Hideki Matsui, Chan Ho Park, Yu Darvish, and dozens of others have come here to find success and even stardom. And, more importantly for people like me, Asian American players have been drafted and worked their way up through the minor leagues to become everyday players and even stars for just about every team. I’m a cohost of a podcast devoted to Asian Major Leaguers called Asians in Baseball. My co-hosts, Kim Cooper and Naomi Ko, are millennials who love the game, and we struggle to keep up with all the players of Asian descent.

And Shohei Ohtani has played 6 seasons, 4 as a two-way star, for the lowly Angels. So obscure are the Angels that the world seems to be just now realizing he exists. ESPN, Bloomberg News, and Spectrum Sports News have reached out to the Asians In Baseball Podcast asking us if the Dodgers are now Japan’s favorite team, which tells you just how important the Dodgers are. It also tells you how irrelevant the Angels are on the global stage. No one ever asked us if the Angels were Japan’s favorite team.

But my story as a fan all goes back to Charlie Hough, long retired now, but still in my thoughts as a Dodger fan. Would I have noticed Nomo, Park, and Ohtani without meeting Hough? Of course. But that memory of Hough’s broad smile, his eyes meeting ours, his hands on our shoulders, connected us to the game, physically and emotionally.

Just last year, I was wearing my old Nomo jersey at a bar, and a Hispanic man walked up to me to compliment it. We reminisced about the Nomo-mania days. And just this week, I was at the 26th Ave taco stand in the Arts District with some friends when a crowd of people showed up just after the Dodger game ended. Multiple White and Hispanic men wore number 17 Ohtani jerseys. Two blocks north is a huge mural of Ohtani on the Miyako hotel on 1st Street.

So now when people ask me what it means to have Ohtani and Yamamoto on the Dodgers, my mind draws a line from them back through Dave Roberts, Kenta Maeda, Hyun Jin Ryu, Takashi Saito, Kazuhisa Ishii, Hee Sop Choi, Chin Lung Hu, Chan Ho Park, Hideo Nomo, and perhaps just as importantly, Charlie Hough.

For me, that list of names extending back through time tells me just how far we’ve come as a nation and as a community here in Los Angeles. As a kid I never dreamed of a day when wearing a Dodger jersey with a Japanese or Asian name on the back would be a sentimental connection to people of all races in my community. Dodger Stadium has always been a favorite place. The kindness of Hough made me feel less invisible there, and the Asian players have made it truly feel like home. They have nights dedicated to Japanese, Korean, and Filipino Heritage at Dodger Stadium now. And while most stadiums are packed with majority White folks, some teams have quite diverse fanbases.

Every time I go to Dodger Stadium, I take my seat and picture a young Japanese American family coming into its own on the magnificent green outfield grass before watching the greatest baseball player of all time, Shohei Ohtani, step into the on-deck circle.